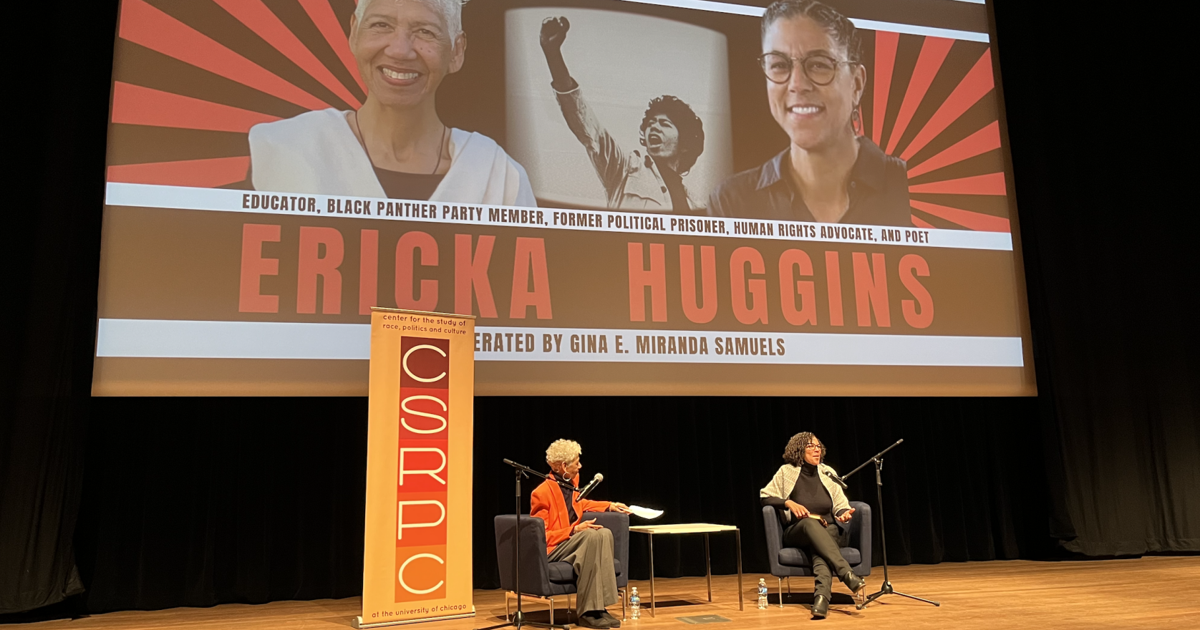

Ericka Huggins, a former leader of the Black Panthers turned artist and educator, took the stage at the Logan Center for the Arts, 915 E 60th St., in style. Invited to give the Annual Public Lecture for the University of Chicago’s Center for Study of Race, Politics and Culture on April 26, Huggins wore a bright orange velour blazer and silver hoop earrings that matched the color of her hair.

“I may not seem so, but I’m a playful person,” Huggins said, introducing herself to the audience. “I was thinking when I walk out this morning into the sunny streets of Chicago as opposed to the rainy streets yesterday, how many smiles can I give or receive?”

“I rapidly had ten ways to share a smile. Not just to give one, but to share it. Some people were shocked, some people were right there, some people were ready to give it before I did,” Huggins continued. “It was just a beautiful thing.”

Huggins joined the Black Panther Party (BPP) in 1968 at the age of 18, fast becoming a leader of the party’s Los Angeles chapter with her husband John Huggins. Following his untimely death in 1969, Huggins moved with their new-born daughter to New Haven, Connecticut, where she started a new party chapter.

Shortly thereafter she was arrested along with BPP co-founder Bobby Seale on charges of conspiracy for the murder of fellow Panther Alex Rackley. Though the charges against her were ultimately dropped, Huggins spent two years awaiting trial, 14 months of which were spent in solitary confinement. It was there that she learned to meditate, which became a life-long practice.

“It keeps my heart clear. It keeps my head clean. I’m not saying that I never have thoughts or worries or emotions that don’t serve me. I’m just saying I have something that helps me quickly push the reset button,” Huggins said.

This ability to recompose herself showed up in her unflappable demeanor when an audience member commandeered the microphone during a Q-and-A session, launching into a monologue about his politics.

“The question is why, despite thousands protesting the murder of Laquan McDonald here in Chicago, millions protesting the murder of George Floyd, Black life has gotten worse,” said the speaker. “The answer lies in the contradiction between the aspirations of workers and the oppressed and the liberal program pushed by their leaders, by the union leaders, the Black leaders, the politicians.”

As the speaker continued, Huggins calmly interrupted, “May I speak? I’m sure that everybody is recognizing what just happened. Now, we can stay there, or we can move on. So, was there another question?”

After her release from prison, Huggins took over the Panthers’ Oakland Community School, a tuition-free elementary school based in Oakland, California, where she was director from 1973 until 1981.

“We taught children how, not what, to think,” Huggins said. “I think a learning community was established there that could be replicated anywhere.”

The impetus for the school was to address the direct needs of the community, and they didn’t let a lack of money or prior experience get in the way of action.

“Things that go on in family, the needs that can’t be met in a family could be met in a learning environment where there are competent and compassionate instructors and caregivers,” Huggins continued. “We started the school, because a lot of us didn’t have something like that.”

That same philosophy underpinned the BPP’s 64 community survival programs, which included a free breakfast program, an ambulance service, and free testing for sickle cell anemia, a disease that more commonly affects Black Americans than white or Latinx ones.

The Illinois chapter of the BPP’s first office was located just south of the Midway Plaisance. Founded by Fred Hampton and former congressman Bobby Rush, it offered many of these services to residents of the South Side.

Huggins recently published a book of photographs and essays with Stephen Shames called “Comrade Sisters: Women of the Black Panther Party,” commemorating the young women whose involvement in running those programs is often occluded by the attention given their male counterparts, either for their outspoken radicalism or their grisly deaths.

Writing poetry sustained her through the oft difficult times in the party. In contrast to the French notion of “l’art pour l’art,” meaning that true art need not serve any practical purpose, Huggins and others like Emory Douglas, whose posters had played on a projection before the talk started, felt that “we don’t need art for art’s sake. We need art for the people’s sake.”

“When we stop doing our art and call ourselves artists,” said Huggins, “We’re forgetting that not only can we be artists, but art sustains movement.”

Although Panthers ultimately dissolved in 1982, Huggins’ passion for activism hasn’t dimmed. Since then, she’s campaigned about the HIV/AIDS epidemic, worked with incarcerated youth, and taught Black and gender studies at public universities and colleges in California.

Her tact and experience as an educator showed through in the way she deftly handled questions from young people.

Savannah, a 17-year-old junior in high school, asked Huggins for advice on what current activists should be fighting for and how to get others involved.

“What do you believe is a next step? I don’t really know what’s the answer for how to bring people together,” Huggins responded. “But do you know two or three people that could come together with you, right in this room? Start there.”

“The Black Panther Party started with Huey and Bobby, period. And it spread so quickly. Black Lives Matter was Opal, Alicia and Patrisse. And it spread. If we think about who’s not going to do something,” Huggins continued, “that’s where we’re putting our energy. Is that where you want your energy to go?”

As a piece of parting advice, Huggins offered, “Determine what it is you dream to do. And I don’t mean dream in a superficial kind of way. In other words, intend to do the thing you think is important, no matter what anybody else says.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.