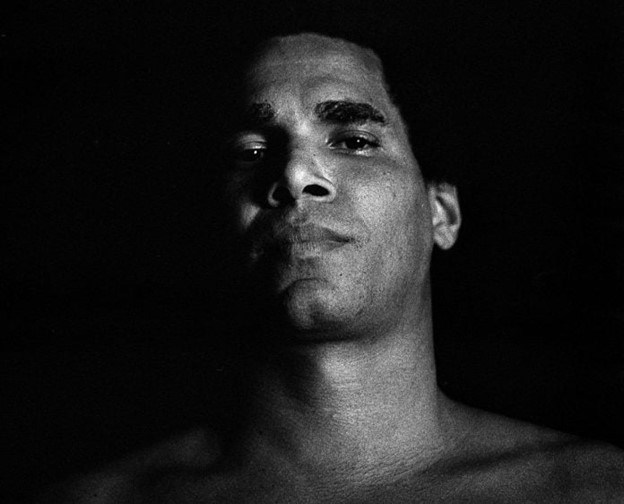

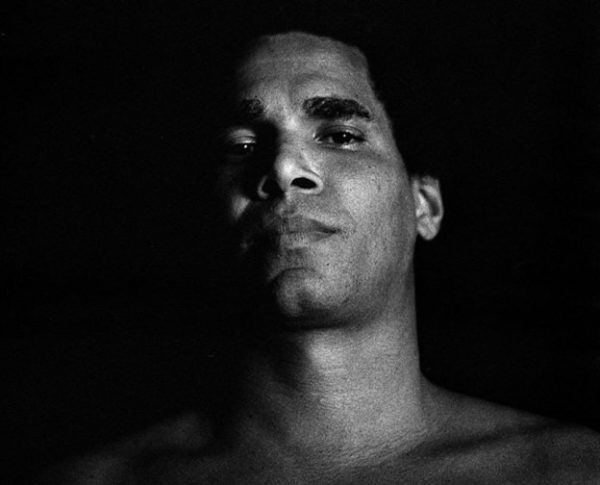

Luis Manuel Otero: “You wake up at six in the morning with a bell that sounds like the cry of a madman”

By Carlos Manuel Alvarez (El Estornudo)

HAVANA TIMES – More than two and a half years have passed, half of his sentence, since the jailing of artist Luis Manuel Otero, one of the most well-known Cuban political prisoners. He was subsequently tried by the Municipal Court of Marianao, Havana, and sentenced to five years in prison for the fabricated crimes of disrespect to patriotic symbols, contempt of authority, and public disorder.

From the maximum-security prison of Guanajay, Artemisa province, Otero has continued to deliver, now with the unique material of loneliness and the passage of time, artistic interventions like “Portrait in charcoal of Schrödinger’s cat”, where he sells and distributes his days in prison. In his cell, Otero draws as much as he can, permeated by the moods and the forlorn faces of other inmates in a penitentiary that the artist describes as “a cathedral of evil”.

For more than a week, there has been no news from him, but up until March 14th, through the occasional phone calls he is allowed to make, with the help of curator and friend Claudia Genlui, we were able to converse with the leader of the San Isidro Movement. His voice, kidnapped, preserves the eloquence and the impetus that reminded a country of that phrase repeated by the furious youth of the French May: “tout est dans tout et tout est politique” (everything is in everything and everything is political).

Tell me about a day in prison, what are the routines from morning until night?

I say it in a text I’m working on now. I say that this is like a kind of theater set, where every day is the same. You wake up at six in the morning and breakfast is disgusting. Imagine, in a country where children don’t have milk right now, they don’t have bread, what can there be left for a prisoner? Lunch is at eleven in the morning and dinner is at six in the afternoon, all in wretched conditions. I draw and paint a lot, try to find something new. You know I’m a guy who gets bored quickly. Fortunately, I still come up with things.

You chat for a while with a prisoner, discuss some topic, like how many eggs an ostrich lays, for example. I try to watch some TV, find a program that interests me. The other option is to become a soap opera fan and cry so that the good guy isn’t killed or so that the bad guy doesn’t win and things like that. You have an hour of yard time a day with a little sun, which is also another scenario. In the end, there’s a moment within three years that is the same, the cycle is the same. You’re still being watched. If you talk on the phone twice a week, they watch your phone. And you know you’re being watched every minute, everything you say or talk about.

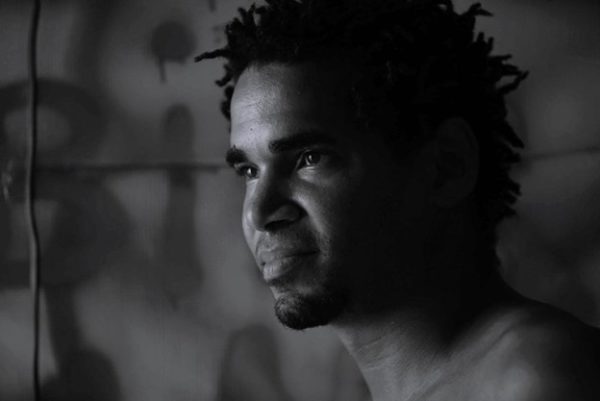

The other thing is art. I paint, I have images of all the faces. You wake up at six in the morning with a bell that sounds like the cry of a madman. There’s a light bulb. You sleep with the white light on all night. Mind you, the light bulb is sometimes bad and sometimes good, because that’s the moment when you’re alone, where no one talks, where no one says a crazy thing that if someone killed someone, that if someone stabbed someone, that if someone stole something. You’re alone with your demons, with all the spirits that peek into your head, and there you take advantage. If there wasn’t the light bulb, it would be totally dark, but when it’s time to sleep, you also wish the light bulb would go out. It’s a great dichotomy.

That’s my day-to-day in here. Images that come to mind, sad faces, depressed people, people crushed, people without hope, many young people who today are put away or they ask for ten, fifteen, twenty years. All those faces, all that energy in a space like this, which is about to reach a hundred years of suffering, you have to channel it somewhere. At some point, through the paintings of these individuals, which get darker every day, you will be able to see what I mean.

What do prisoners usually eat?

Well, the food is pathetic. Rice occasionally… Look, like two days ago they gave a little fish, but we’re talking about them giving it once a month. The other thing is a pasta, something that has no taste or smell, or a tuber and a soup that also has no smell or anything. That’s lunch and dinner. At breakfast, they used to give bread, but now with the crisis… I repeat, in a country where there is no bread for children, what can they give for breakfast? A soup.

There are some who receive something extra. In this hallway there are quite a few who do, but most of the prisoners do not. The family sacrifices itself to bring you a few things, and when ten at night comes, when the dinner normally came at four or six in the afternoon, you’re ravenous. And the other thing is that the amount of food is the same for everyone, whether you’re two meters tall, one meter tall, fat or skinny. If your family has possibilities, or at least loves you a little, they bring you some bread, some cookies… all the chaos that is this reality.

How do other prisoners behave towards you?

I’m different from most people here. For example, right now they take me to the dentist and others no, so there’s like a certain tension. But I can’t talk on the phone every day and some prisoners can. There are people who admire you, there are people who have certain misgivings, there are even people who are afraid to be with you. If they are with me and there is another prisoner snitching, informing the State Security, about someone who is with me, like a friend, they take them out of here to another supposedly more uncomfortable place. “Friend” in quotes because friendships are not formed here. So, it’s like a kind of strange relationship. Everyone knows who I am, whether they’re with me or not, whether they talk to me or not. Half of them are informing State Security, the other half is afraid, although some dare too. That’s more or less how the dynamics work.

How do the guards behave towards you?

It’s interesting, because here the guards know that you’re a political prisoner, that they can’t mistreat you or anything like that. In fact, I’m a guy who respects people a lot, from the street. I’ve always showed respect. I see them as doing their job, the fault for me being in prison is not theirs. From there on there’s mutual respect. In fact, the guards put the responsibility on the prisoner who watches the hallway, do you understand? who is like “Mr. Discipline”, the famous “discipline” who must make sure people don’t talk about politics, make sure nothing happens. In my case, the guards open and close the gate for me. If I have any doubts or any discomfort, they’re the ones who analyze it, but it’s not like they have much presence or can do much for me. I can disrespect them in the worst way possible, and they’ll simply stay silent, because the order is that Luis Manuel cannot be hit, he cannot be mistreated.

Are they afraid something might happen to you for which they’ll have to be held accountable?

You feel that yes, there’s exceptional care. In fact, when I get depressed, suicide is a normal option within my own life. Then you see that they are like watching out for anything that could happen to me, that I slip or hit myself or something. You realize that the same prisoners are sort of taking care of me. They have prisoners in charge of taking care of me, beyond the guards, even. If something happens, the police come immediately, the doctors come. They don’t want me dead; they don’t want me mistreated. When I stop talking on the phone, you immediately realize that they worry. When I don’t want visitors, because I get depressed and don’t want to see anyone, they worry and get alarmed. Yes, I think they are concerned about my physical integrity, for now.

Do you have the same leadership inside prison as you did in freedom? Do prisoners and guards respect your cause and your thinking?

Yes. The only ones who go out to the yard are from corridor 20, which is where I’ve been since I got here. And when I go out to the yard, you realize that there’s a whole myth around me. People greet me from afar: “Alcantara, you are the future of Cuba”, “Alcantara, I don’t know what”. What really happens is that inside here I don’t want to do any kind of proselytizing, I’m not interested. In fact, on the street, I never proselytized. But yes, you realize that people feel that you are like a symbol of something. The guards too, mind you. All the guards around me know, and you walk and have people watching you. They are like watching and admiring you. Many people know even by hearsay, they don’t even know your story or anything. Simply the myth grows. And the other thing are the differences with me. I spend my visit alone in one place, where not everyone goes, and so on and so forth.

What particular codes have you had to learn in prison?

Normal, the relationship between human beings. I come from a good reality, among friends, people I love, my family, you, where there is trust and respect, in the sense that there is no violence, and the violence there is minimal, nothing that can compare to what’s in here. This is a reality in Cuba where the government, the regime mistreats you, what do you expect between prisoners? So, you have to deal with all that and not worry too much, you have to let things take their course and each one takes care of their reality, you understand? And you’ll share, but if you share everything, you’ll end up with nothing. In fact, are there people who deserve you to share with them? Not really, because they’re informing the guards. There are people who are not so good at all or who disguise themselves as good to make themselves… I don’t know, I can’t explain it well.

What recurrent thoughts accompany you? Is there any obsession that haunts you, any happy memories that you recreate?

In here, I’ve never had nightmares. I’ve always dreamed, I’ve always had very positive dreams. When I go to sleep, what haunts me is art, I can’t stop making art. In fact, when I close my eyes, I get many images of spiritualities that are here, around me, locked in this place that is like a cathedral of evil. And that demands art from me, to go out and meet my friends again, to meet with my family again. My body, I tell you, is constantly in all those positive experiences from the past. That said, after these three years, are people still the same? No, but I imagine they are. When I hear my friends’ voices, I think they are the same beings with the same collectivity and the same positivity, beyond suffering and distance.

Have you ever thought you were abandoned?

No, sometimes you feel like reality stretches. I thought I was going to be here six months and I’m going for three years and counting. Yes, you lose hope or faith at some point and rethink things, especially that. I think three years ago I was thinking one thing and now I’m starting to think about others.

Have you made new friends in prison?

Friends always based on distrust. This is a circus set up around me and the person who approaches may work for them [the ring leaders]. But I manage to detect some people and generate more empathy for their face, for their energy. You manage to communicate or share a little more so as not to lose kindness either, because that’s the idea. Even though you harden a little bit in here, as a result of reality, you shouldn’t lose kindness, do you understand?

How much do your convictions, your sense of justice, help you cope with moments of sadness or weakness?

That’s in my DNA. I think that, despite all the difficult moments, even if I find myself alone or locked in a cave without being able to communicate with anyone, I am like that, that is my nature. Since I was a child, very little, I knew I was going to change the world, without even knowing if the world existed, thinking the earth was flat.

How is time lived, what forms does it take? Do you count the days, forget them? Does it depend on you to remember or forget?

Time in here is not the same as out there. It’s not the same time for me, as it is for a politician, as it is for someone in exile, or as it is for someone in Cuba who is hungry, for example. When you’re hungry, or you’re waiting and you’re missing a minute to achieve something, that time takes longer. It’s the same in here. There are moments that pass faster, moments that pass slower, or moments that have value or in which one is conditioned and that’s where this cat’s work comes out. One of the things that happens in here is that you think your time is worthless? But if you have that conviction, if you’re sure, you know that time has value. The ten minutes before talking on the phone take longer, the five minutes before the visit arrives take longer. It’s the anxiety. Some days are worthless or you’re playing dominoes and the whole day goes by. This causes a crisis about time.

What do you dream about at night?

Dreams of freedom, being on the street, meeting my friends. Yesterday I dreamed I was in some kind of theater where theatrical performance was taking place. My mom was there, for example. My dad was there a lot, and all my friends were on stage. It was like a collective performance for my birthday, a kind of crazy thing.